With Spring Rain

This April I am making lists.

It has been a strange spring this year. Strange, I think, for its melancholy. For most of my life I have lived in places where spring arrives as the spring we anticipate. There are flowers. The trees bloom. The grass greens up and starts to smell sweet again. There are pockets of warm, fresh air that beg us to stop. So we do. We stop and we see spring is here. We are free of winter. We are relieved. And yet there is a melancholy that comes with the season. I notice its presence more this year. I cannot recall hearing anyone speak about it, at least not this year. Rather, I find it in songs. “Spring Can Really Hang You Up the Most” is a tune that sits close this time of year. This jazz standard is one I love, and a favorite verse goes:

Love seemed sure around the New Year,

Now it’s April, love is just ghost,

Spring arrived on time, only what became of you, dear?

Spring can really hang you up the most.

Spring arrived on time, only what became of you, dear? This is a line that summons our best losses, our finest regrets. This spring I have been listening to Ella Fitzgerald’s rendition from the 1961 Clap Hands, Here Comes Charlie! album. Lou Levy chords in the tender beginnings. Then we hear Ella’s voice. That wonderful voice that catches slightly in the beginning but soon takes us to a time when, Once I was a sentimental thing. There are several great recordings of the song. The Carmen McRae version from her 1971 self-titled album Carmen McRae surprises me with its modern sound. McRae’s reluctance and hesitations keep me listening, keep me guessing, too. I am not confident about her feelings. Will she stay or will she go? Either way, McRae can trap us in a sentimental spell simply by holding a note. There is, too, the memorable Stan Getz version from his Getz at the Gate album. I hear the Getz version and imagine myself entering some posh apartment in a faraway city. The lights are low. The shutters are pulled to the middle height of the windows. There are half finished letters on a hardwood desk. A vintage French leather chair. A table beside it. A lamp. All the while, Mr. Getz takes time with the tune, calling me back to any number of springs, any number of loves. And I don’t dare to move.

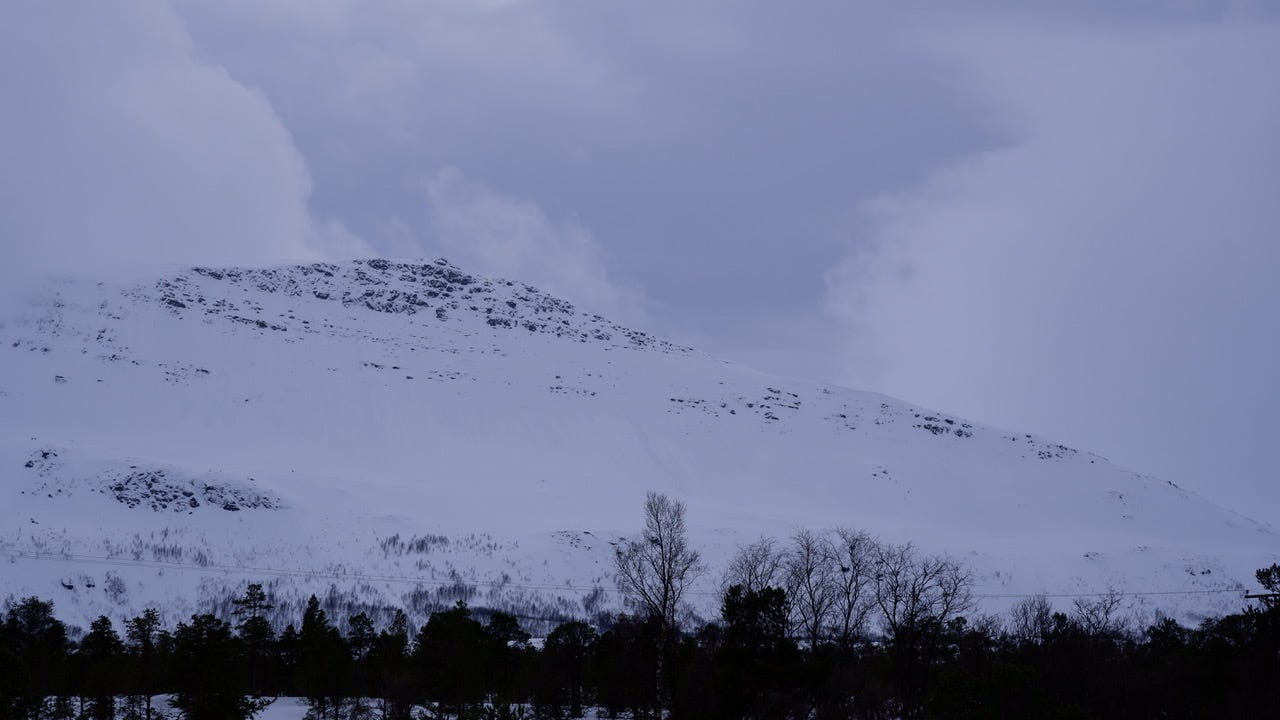

But in the here and now of where I prepare for another day, I have been watching the snow melt. There is a patch of open ground that has formed next to the house, on the sea side of the Tunheim. This narrow strip of thawing earth will gradually spread across the yard and down to the sea. The snow melts away, and beneath it is grass. As matted, as molted, as grey as this patch appears, the grass will turn green in the coming weeks, and we will marvel once again at this most ordinary of changes. Green grass.

Spring above the Arctic circle comes round slowly. If we are overly anxious for what will come then we risk experiencing a vague sort of emptiness, living as we do this time of year in a kind of purgatory, where there is snow everywhere, yet we certain greener days are on the way. Only they haven’t arrived yet. Day by day we watch the snow melt. We watch it drip from cliffs and from the rooves of our homes. I noticed that the crocus bloomed on April 13th and watched as they were obliterated on the 15th when the snow returned. The dates seem to matter, but I don’t know why. Recalling the dates, I realize that I have been obsessed with making lists this season. My tendency is to note what is here. Two weeks ago on the drive home from the school, I saw my first tjelden of the season. There were two of them, sitting on the seaside rock that the Arctic terns will inhabit in another couple of months. They looked remarkably passive. Their feathers were slightly puffed. Their very round, very black beady eyes stared out at the hav, though somehow they looked calm. I wondered then if they ever dreamed of other oceans. When I got home, I unpacked my school bag and took out one of my notebooks and scribbled a few sentences about seeing the birds, adding them to my list.

A sample from this year’s list include:

I went to have my blood drawn. While I waited, an older Norwegian man, also waiting for his number to be called, kept shouting the numbers as they appeared on the call board. So, when number 2 flashed on the board, this old Norwegian man called out NUMBER 2! then NUMBER 3! and so on and so on. He did this in English, too. I don’t know what surprised me more, his English or the fact that he was bold and loud.

Just two days ago while driving to the school, three ravens swooped down on my car. This happened on a stretch of road that cuts between a pocket of conifers and the sea. I suppose there is nothing remarkable in this, except that for an instant I felt as if I had passed between worlds, this world and a world more enchanted.

I went outside to stand on the porch. The porch faces due east, and I wanted to feel the sun on my body. When I went outside, nine grouse flushed from the tall trees growing beside the road. Nine grouse!

***

Since the time I was 17 years old, I have kept journals. I cannot guess how many lists I have made over the years. In my earliest notebooks there are lists of fishing flies, weather and river conditions, trout caught. Later, in my young 20’s, there were lists of jazz tunes I heard or wanted to hear, noting, as I did, various artists and renditions. It was also in my 20’s that I began to record moments that I sensed would reach beyond their time, moments when the edges of the present are at first clear, but soon those edges thin and open into story. These moments in my 20’s often happened in the world of fly fishing and wrangling. I was a guide in those days and lived my life according to rivers. There was a four day camp I made with my mentor, Gene Story. We were guiding a couple into a deep wilderness and to a small creek where we could fish for native trout. Gene was a man of limited patience. He woke up early and started straightening gear, re-packing. He couldn’t settle into the rhythm of a trip. Each morning of that trip, Gene started with a swig of Schnapps. He told me eighteen year old, teetotaler me that it was great mouthwash. On the second morning, he handed the bottle to me, and I took my first sip of this new mouthwash. As I nipped at the liquor, Gene said, “It’s okay if a few drops trickle down the old pipe.” I nodded. “In fact,” he said, “it might be a good thing if it does.” So, I took another sip. “Good isn’t it?” I nodded again. “Yep. Pretty god damn good mouth wash,” he said. “Now let’s find those bastards some fish.” It was a beautiful morning, that morning, one of those mornings when the mountains are clear and full of sunlight and life. Pure, almost liquid sunlight dripping through the green roof Aspen tops. The creek was alive with trout, and anyone could have caught a fish that day, even these bastards who couldn’t throw a fly line to save their lives. Schnapps in the morning. Trout in the afternoon. I became aware that the edges of that moment would loosen and become story, and they did. With my 30’s came the names of streets in cities with exotic names and windows where I stopped. The windows of the puppet shop in Budapest where wooden puppets were on display. The owner of the shop demonstrated for customers how to bring the puppets to life while making himself disappear. There were windows in Amsterdam, where orange, elegant rooms were filled with paintings, polished tables, lamps, and the one instance when a woman saw you noticing her and how she turned slightly to offer a more intimate view. She was aware, of course, of her allure. Women who carry this are as rare as their powers are unlimited. In my 40’s I began to keep lists about what I intended to write and what I will never write. There are lists of places I desire to go and will likely never go. Books I hope to read and will likely never read. I have listed what people have said to me. I have listed quotes and passages from books and stories and poems and plays I love. More often than not, I find myself making lists without appreciating that I am keeping something of a record, except for this season. This season I have been intentional about listing what is here.

Umberto Eco said it plainly, “We like lists because we don’t want to die.” Now in my 50’s, I find this difficult to argue with. Many of my present moments are filled with my past. I can hike to the local trout stream and see who I was as a young boy, trudging along a trout stream near the town where I grew-up. I was on a quest as a boy, searching for water where fish thrived, learning how to fly fish, questioning and discovering what sort of fly fisherman I would become. Although I have answered those questions, I can walk to the local river today, which is thousands of miles from where I grew up, and those old questions are with me—that boy is with me. The rock pool of my local stream bears little resemblance to the rock pool where I caught my first trout, but I can imagine them as the same pool. I am likely to rest, and have rested, along my local water where I will, with the bliss of imagination, reconfigure the pool into that first pool of my youth. Something similar can happen when I am in the city. I can walk about the city and hear seagulls calling. Then suddenly these arctic seagulls echo the seagulls that in my childhood followed the ferry between Galveston Island and the Bolivar peninsula. I rode the Galveston ferry often as a child. Those were the years when my grandparents, my Dad’s mom and dad, still owned a beach house along the Gulf. We went there often as a family when I was young, but as I grew older, I went more often with my dad. Dad and I loved staying at my grandparents’ bedraggled beach house for days at a time. We loved riding the ferry to Galveston. This same place, the same beach house and ferry were part of my father’s childhood, as well, and I can picture him, Dad, staring ahead towards Galveston as we ride the ferry, with his hands tucked into his coat pockets and his feet crossed, right foot over the left, as he leaned against the ferry rails. Even as a child I recognized that Dad saw things I could not see. I wish that I had knowledge of who or what had entered my Dad’s present, but I did not understand how to ask such questions as a child, no child does. And always, the seagulls careened over the back of the ferry. They called and snapped and begged for food from the passengers. We sometimes fed them, Dad and I, by tossing strips of Wonder Bread into their messy cloud. Now in the city, in my present, on some rainy day when I am walking the streets to see how the city withers from the rain and enters a silence, I will cross an alley or move along some street where everyone has gone indoors and all the light I can see comes from warm coffeeshops, and I will hear the gulls calling still. A few steps further along, and I will be in Galveston and on The Strand with my father, debating if we should go to Colonel Bubbies again, not because we have anything to purchase or even much of a desire to survey the latest Army surplus, but because we always go there.

I remember these things, and this year I am more conscious about listing them. Perhaps one day I will need, truly need, the moment when an old Norwegian man shouts numbers for those of us waiting for blood tests or the event when a boy at the elementary school randomly threw a heavy clump of old snow at the windows of the woodshop. The compulsive action of this 8 year old boy was taken while he waited with his peers for the bus home. But it’s not really the boy throwing the snow that I will remember most, rather how Lars and I looked at each other in befuddlement after this kid threw the snowball. We laughed and laughed at what was an obviously dipshitted thing for this boy—for any boy—to do. It was a wonder of a kind, and neither of us had an explanation for it.

For most children, their sense of time is informed by what they immediately need. “I feel hungry,” for a child means, “when can I eat.” “I am bored,” for a child means, “when do we get a break.” Physical requirements and impulse are serious time markers for children. Their lack of awareness is sometimes baffling. They notice little of what is outside of themselves. They notice little of how a solid effort in the classroom can translate into a better day, of how good manners will bring good returns, of how any given day may be the best day of their lives. These possibilities escape the attention of most children. Perhaps this is what nature intended. If we thought too much about consequences and the future, we would hardly take a step. Despite my better judgement, I do sometimes catch myself advising children. Pay attention, I will say. Whatever is upsetting you probably isn’t a big deal. Life will get a lot harder. You’re acting like an asshole. Don’t act like an asshole. Think about it, I often say. I could plead with children that their better moments will travel with them for the rest of their lives, if they wish. I could admonish them to, “Put this moment on your list!” Except, I do not. I stare. I shake my head. I laugh with them. I let them know the end of the world is not at hand, despite their getting hit by a ball in a game in which the object of the game is to hit everyone with a ball. I apologize for my limited Norwegian, for my limited hearing. I teach them to draw roads that fade into a horizon. I push them on the swings. I tell them that 9+3 will always equal 12 and that 3+9 will also always equal 12.

Last April I was flying over Greenland. This April I am making lists. I am teaching kids how to count by 10’s. I read Frog and Toad Are Friends to trump their machines. I am grateful for their hugs.

It was during uteskole some weeks ago that I asked Lars if he thought the children could really see where they were skiing, if they could really appreciate the moment they were having, as we skied in the hills behind the school and afterwards made a fire and learned about different animal tracks and droppings.

“I don’t think so,” he said, “or not yet. It can take a while.”

I told Lars that I felt like I could see when I was a child. I saw the color of the trees. I paid attention to weather and how particular days made me feel happy or sad.

“Maybe that is because you were dying as a kid.”

“Maybe.”

“For me it happened when I was 14 or around 14.”

“What happened?”

Lars then told me how growing up he had wanted to be a capable sportsman. He desired to be a respectable grouse hunter. To prove he was a respectable grouse hunter meant, in his young mind, that he needed to shoot grouse each time he went afield, which isn’t unreasonable. A competent fisherman catches fish. A competent bird hunter kills birds. “Good days were measured by my success at getting birds,” Lars said. “That was my measurement.” When he didn’t bring a bird or two home, Lars felt disappointed with himself. He felt that his time in the fjells had been less than what he expected. He had been less than what he expected. His focus on taking birds had narrowed his vision. His appreciation for the mountains that he loved as a boy, that he still loves as a grown man, had been reduced to a handful of feathers.

That was the perspective of the young sportsman until his uncle taught Lars another way. This was an uncle, perhaps it is best to say the uncle, who introduced Lars to another aspect of sport, of being the fjells. Lars said of this uncle, “He taught me not to be so disappointed if I didn’t get anything, any birds. He said the smell of the fjells is here. The rocks. The sunlight. The nature. These things are here, and they will not disappoint us.” That was when Lars began giving attention to where he tromped in the fjells. He learned to let days pass more slowly. He began to learn the lessons neither of us are confident the children in our classes can understand.

This same uncle, Lars later told me, had lost his leg while on a peace keeping operation for the U.N. in Lebanon. Lars’s uncle and another soldier had gone to recover a comrade who had been wounded by a landmine. In the recovery, they found that the entire area where the wounded soldier fell was peppered with mines. The uncle and this other, unwounded soldier stood holding a stretcher, prepared to carry the wounded comrade to safety, but when he, Lars’s uncle, shifted his foot, the mine beneath it exploded. The slight shift in his weight had detonated it, and this was how he lost his leg. Lars said that after his uncle had been blown into the air, he landed on his head. It was discovered that his head was short centimeters from yet another mine.

Today the uncle walks using a prosthetic. Lars says when it rains or if it becomes too hot, his uncle must stop and wait. He must dry the moisture from around the prosthetic. Otherwise, it slips. When he goes out for grouse, he walks 20 maybe 30 minutes. Then he will rest. As Lars has told me, “My uncle hunts slowly. But it is beautiful. We are in the mountains.”

***

Part of me is sad to see the snow melt. Part of me is also glad to see it go. We are all this creature.

We have an egg incubator at the school this month. We have more eggs than students. We check the eggs each morning to see if they have hatched into chickens. On Tuesday, the mother of the student who loaned us the incubator and who also gave us the eggs attended class. She was there to look at the eggs with us. I didn’t realize it, but there is a light on top of the incubator upon which we can set an egg and see if anything is inside and thriving. That’s what we did under the direction of the mom. We took turns placing an egg on the light and looking for life, including me and Lars. The children are excited for when the chickens arrive. I suppose I am, too. It feels pretty good to work at a school where we check for chickens in the morning. The eggs and the incubator are in a room attached to one of the classrooms. There are Legos in the room, a few books, and a nice big window that offers a view of the swings and the forest that grows there. The snow is melting, and we made our final ski trip of the school year last week. Lars and Anne led us to a place where a tree grows out from the side of a cliff. The tree is hidden, too. You would need to know where to go to see it. I was probably more delighted than anyone to see this tree—a small tree, growing right out of the rock. I don’t know why I felt elated, almost tearful to see this tree. Maybe it’s the luck of it all. I added the tree and other parts of the day to my spring list, which may or may not turn into a summer list. I do not yet know.

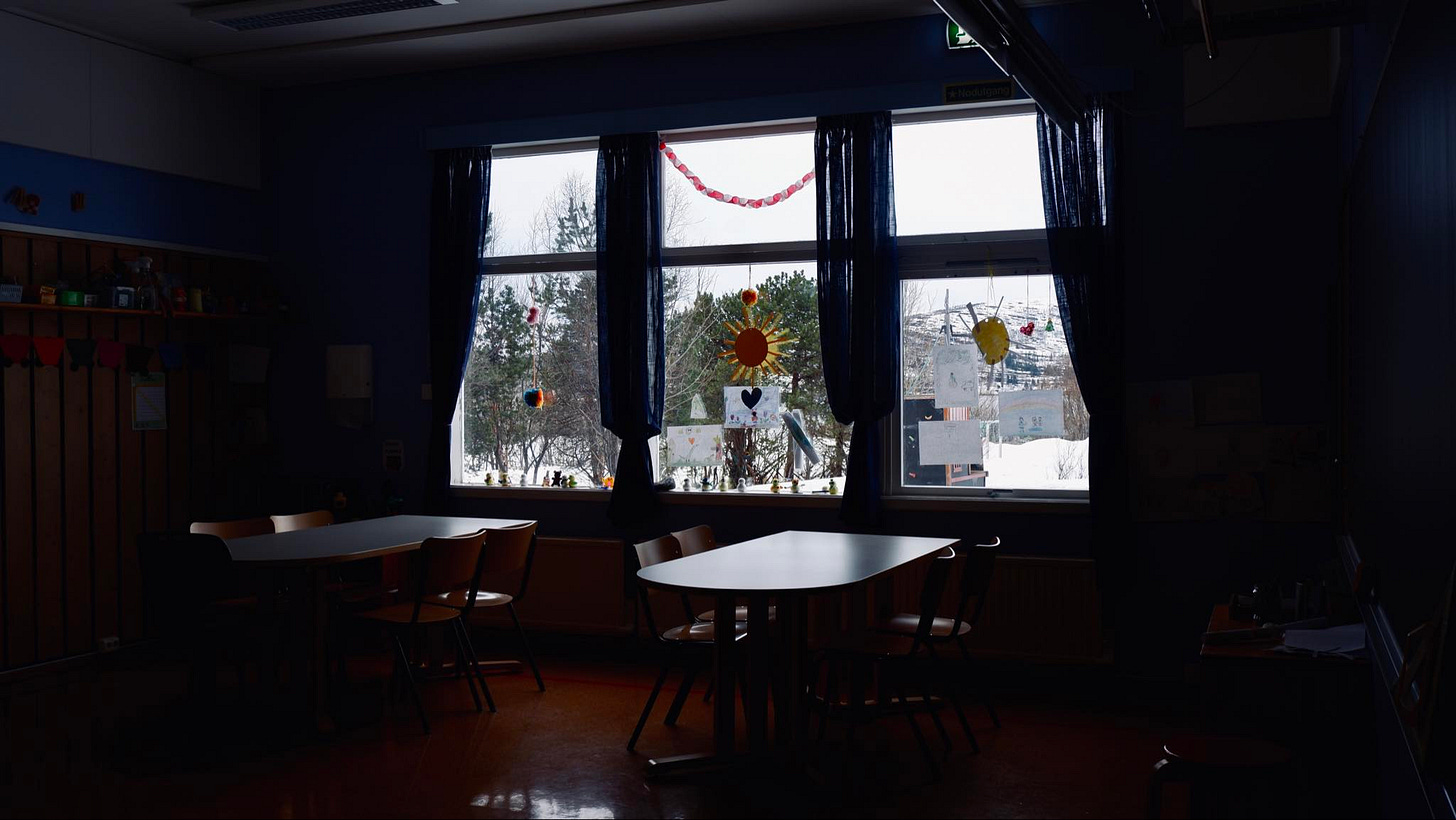

There are days when I am the last one of us to leave the school. After everyone has gone, I make sure the classrooms are tidy. I check the kitchen and put away the clean dishes and load the dishwasher with the dirty ones, if there are any. Then I turn out the lights and lock all the classroom doors. Before I leave, I take a moment to notice the emptiness of the rooms and hallways. I do not hurry. I let the day drain out of me, let the stress of the day diminish into something else, because there is stress when managing kids, and I hope that I have managed them well enough. The kids have returned to their other lives—to their parents, to their phones, to their computers, their video games, to their pets, and to whatever obligations they might have. Without them here, I can drift into this life that I go on imagining, and occasionally, there is some other moment or something else that glimmers with a past. I cross the parking lot that in mid-April still had snow in it. More and more birds are returning. One evening I watched a magpie fly over the parking lot. The bird flew with a stick twice as long as its body. This was the first magpie of this season that I have seen doing this, toting a stick to some new nest somewhere. The way the bird flew was to flap its wings then hesitate, then fall then flap then hesitate. The motion looked a like a succession of waves or how we swim our arm when we drive with the window down and poke our arm outside and lift our hand. That wave. That swimming curve. I watched the magpie until I couldn’t see it anymore then kept on my journey across the parking lot. And it is a journey, or it should be, truth be told.

The last verse of “Spring Can Really Hang You Up the Most,” by the way, goes like this:

All alone, the party’s over.

Old man winter was a gracious host,

But when you keep praying for snow to hide the clover,

Spring can really hang you up the most.

Notice that mixture of snow and clover, of warm and cool, of what is here and what we will miss. All these melancholy songs.

Damon Falke is the author of, among other works, The Scent of a Thousand Rains, Now at the Uncertain Hour, By Way of Passing, and Koppmoll (film). He lives in northern Norway.

If you enjoyed this post, hit the ♡ to let us know.

If you have any thoughts about it, please leave a comment.

If you think others would like it, hit re-stack or share:

If you’d like to read more:

And if you’d like to help create more Juke, upgrade to a paid subscription (same button above). Otherwise, you can always contribute a one-time donation via Paypal or Venmo.

thank you, damon for this. gosh, no one captures the wonder of fleeting/unremarkable moments like you. (yet they become remarkable in your hands) . so blessed to read your words.

So wise, beautiful & evocative. Will have to give the notion of Spring being melancholy some thought!