The Flags of Memorial Day

My relationship with the flag is not as simple as it once was.

Do the dead belong to us? Or do we belong to the dead? We tend to their memories, their legacies, their remaining property and their graves. Are we their servants? The answer does not depend on belief in an afterlife. And there doesn't need to be an answer. The actions that we take, the burdens we carry for the dead are enough of an answer. We keep their memory alive until we are dead. If they blew some stardust into the universe, they may not need us, but there’s a reason grave markers are made of stone. We are ultimately dust. We blend with the stars and become nothing. A stone marker will decay, as well, but it buys enough time for us to tolerate the idea. "Forever" is a lot to bear.

Today is Memorial Day - a holiday with origins both murky and clear. What’s clear is that it began as “Decoration Day” and its purpose was to decorate the graves of Civil War Soldiers, thus honoring the dead for their service and sacrifice. Honoring the dead and, specifically, the military dead, is a practice that extends back a long time, centuries before the U.S. Civil War. But the first call for a national Decoration Day was made in 1868 by General John A. Logan, who was head of The Grand Army of the Republic, an organization devoted to Union Civil War veterans.

Other states, organizations and individuals have claimed to originate the holiday, but the arguments don’t concern me. What is irrefutable is that the different iterations of it - for both the Union and the Confederacy—all merged into a single national holiday that was observed on May 30th of every year. A time of year when flowers in the north would be in full bloom.

Ultimately, it took an act of Congress, the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, whose purpose was to ensure three-day weekends for Federal employees, to set “Memorial Day” as the name and the last Monday in May as the official date. This act passed on June 28th, 1968. Two other holidays that get conflated with it are Armed Forces Day, a May holiday that honors those who currently serve in the military, and Veterans Day, on November 11th of every year, a day that was originally meant to honor American military deaths in World War I.

Memorial Day is now widely seen as the beginning of summer, which is not disrespectful on its own. If that is the ONLY view that people have of it, though, it minimizes what is otherwise a solemn day. As far back as the early 20th century, some Civil War veterans complained that the holiday had become simply an occasion for “games, races and revelry, instead of a day of memory and tears.” At the risk of appearing to be a stick-in-the-mud, I agree with this opinion from over 100 years ago.

I grew up at the tail end of the baby boom. I was a young child in the 1960s, living in the suburbs among many war veterans who were then young men with young families. None of them ever wanted to talk about the war. They wanted to live their lives. It seemed to me that they mainly wanted to forget about the war, especially the combat vets. My friends and I, of course, donned plastic helmets, carried toy guns, and played war games all day. We had flags and pretended to talk to each other with fake walkie talkies on fake beachheads.

At the same time, the anti-war movement - centered around Vietnam mainly - was raging. Protests were on the television set, our old black and white TV set, and in the newspapers all the time. The National Guard opened fire at Kent State. Construction workers yelled “America—love it or leave it” at kids in the street. I was as glued to this news coverage as I was to the snippets of news film every night from Vietnam—footage of firefights and helicopter attacks.

I grew up on movies that glorified war and war heroism. “The victor gets to write the history.” It’s a phrase that has recently been questioned, along with most everything else. Still, there is some truth to it, and there were few films then that truly examined war’s philosophical underpinnings. There was nothing to examine. Adults who had lived through Hitler’s expansionism, Pearl Harbor, and the earlier Spanish Civil War had no need to look too deeply. They had signed up—not happily, but from a sense of duty, patriotism and the desire to protect their way of life—to put themselves in harm’s way, to fight the aggressors in “the last good war,” as it was called later on. There had been years of isolationism and a powerful “America First” movement. After Pearl Harbor, though, the nation reached a mass, unspoken agreement, that this was a fight we had to fight.

These were not the same men who had gone to Europe to fight in the first World War, the “Great War,” “the war to end all wars.” That idealism was gone by 1941. It disappeared in the killing fields of Flanders and under the rattle of mechanized killing. The World War II generation had no illusions about the nobility of war. It was simply a job that had to get done. When it was over, those who survived wanted to resume their lives. The soldiers from WWII, the ones who had fought and bled and lost years of their lives, may have been happiest to quietly mark the day on their own, to enjoy the peace they had won by grilling hot dogs in their backyards, by taking the day off from work, and moving on.

The warriors of my dad’s generation—if they celebrated at all—celebrated Memorial Day from living memory, not recorded memory. It’s sad, but we have always had living memory along with us on this day. This country fights with less unity now, with far less shared sacrifice. But we have been in a state of war for the better part of the past 80 years. We have plenty of veterans who have seen battle. We just ended a 20 year war but most citizens were barely aware of it. Our wars and our veterans have become, if not forgotten, certainly invisible.

There is living memory, there is institutional memory, and there is recorded history. We can look back through many lenses. Our view of the past changes as time goes by. We have enshrined Memorial Day as an important holiday and we have created rituals and symbols with which to celebrate. Many still decorate graves on Memorial Day. We lower flags to half mast and some of us contemplate the nature of sacrifice and remember those who were lost. We may think about what they did and why. Many of us, though, see only a day off from work and blindly focus on where to travel, what to buy, what to eat, how to use this day for pleasure.

I will try not to engage in moral relativism, will try not to judge those who don’t know what this holiday means and try not to begrudge those who treat it blithely. What has happened to Memorial Day is just another example of what all holidays have become. They are, if not meaningless, then diluted—another excuse to focus on ourselves. And what’s wrong with focusing on ourselves, you might ask? What’s wrong with turning inwards?

The extreme narcissism of this moment is the subject for another column, but the way it affects our celebration of holidays is not. Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, and countless other holidays are in the calendars, along with state holidays that celebrate Jefferson Davis, Kamehameha, “Pioneer Day” and more. “Purple Heart Day” is on August 7th, which I think of as the invasion of Guadalcanal, but I’m not sure they are connected. “National Doughnut Day” may hold more significance for some than others.

While Valentine’s Day is not just a Hallmark holiday (it has some basis in history,) it is emblematic of every holiday that exists to sell cards, make meal reservations and celebrate out of a sense of obligation. Do I sound grumpy and bitter? There are so many holidays that you could celebrate something every day of the year. Most are fabricated for some reason and then left to take on a life of their own.

The religious holidays are in another class. Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus and other religions each have their own unique holidays and customs. Some are widely celebrated and others are not. Some may have become celebrations of eating and consumerism. Some have not. They all serve a function of some kind. Another subject, another day.

Banks have listed holidays, as well, based—for the most part—on whether or not it’s profitable to stay open for business on those days. Which is honest, in a way. If something is a “bank holiday,” then you know it’s serious.

The U.S Federal Holidays are as follows:

New Year’s Day

The Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Washington’s Birthday

Memorial Day

Juneteenth

Independence Day

Labor Day

Columbus Day

Veterans Day

Thanksgiving Day

Christmas Day

You could write a good history of America by talking about the evolution of these holidays, how they came about, how they have been observed and how they evolve. The flag often figures prominently in their observance. It would be uplifting and infuriating but, ultimately, I believe it would arc towards good. It feels like we are currently caught in a difficult period of evolution and I’m not sure I’ll be around for the next uplifting time period, but I’ll try to believe it will come. Giving up is easy; keeping some kind of hope takes more work. More faith? I don’t know. Maybe it takes more action and active engagement.

For better or worse, we belong to places. Humans are tribalistic. Culture honors tribe as much as, if not more than, it honors our basic humanity. We belong to a time and to the people around us as much as anything else, whether we want to or not. I was born an American. I was raised in this country and am claimed by this country through various ties—my language, history, passport and memory.

In my elementary school, a public school in Yonkers, New York, we began every day by standing up, putting our hands on our hearts, and reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. We began, “I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the Republic for which it stands…” in the cadence that we unthinkingly adapted. This pledge has changed over the years, as has so much about the country and the flag, which gained its 50th star in the year I was born. As a child, I loved the idea that the flag could change and add stars to represent growth.

What does the flag mean to me now? I’m not as sure as I used to be. I have always believed in the democratic process, however flawed and ugly it can get at times. For most of my life, I was impressed at how our country would hold elections and peacefully change power. I always took it for granted that America was an example of humankind at its better, if not its best. Some things have changed in the 21st-century about how we govern ourselves. Our divisions, which used to be a source of strength, now seem to be more a source of conflict. The protests, which used to demonstrate our diversity and freedom, now seem to show our anguish and division. I could go on and on, but I will leave it for now. My relationship with the flag is not as simple as it was when I was a child.

I was riding my bicycle up the Hudson River bike path yesterday, past the Intrepid - the floating museum that used to be an active aircraft carrier in World War II. The Intrepid saw its share of combat and was, in fact, hit by a kamikaze attack. A few piers north, for this holiday weekend, as always, the Navy had sent a ship. In the old days, people would say “The fleet’s in town,” but I think it was just one ship and possibly its support craft. I asked one of the Marines guarding the pier what ship it was and he said “The Bataan.” I kept riding, but my head started swimming.

I thought of the peninsula in the Philippines where the battle took place that gave this ship its name. How, at the start of World War II, this country was so unprepared and our resources were so thin that we had to call back convoys meant to resupply the soldiers trapped on Bataan. I thought of how they fought on anyway, with limited means. The situation was so hopeless that they came up with some doggerel. It kept going through my head on this bike ride up and down Manhattan yesterday, a fine May day in 2022, something composed by condemned men 81 years earlier:

“We’re the battling bastards of Bataan;

No mama, no papa, no Uncle Sam

No aunts, no uncles, no cousins, no nieces,

No pills, no planes, no artillery pieces,

And nobody gives a damn.”

Those that survived the battle were starving and out of ammunition when they finally surrendered. MacArthur had been ordered by President Roosevelt to escape from Corregidor, as his capture would have been a major triumph for the Japanese. He was so scarred from the retreat that he vowed “I shall return” to the Philippines, despite the War Department - this was before it was renamed “The Department of Defense” - who requested that he change it to “We shall return.” His transport planes would forever after all be named “BATAAN.” For the young men who did surrender, what followed was the Bataan Death March and then brutal life in camps for the duration. Families at home did not know what had happened to many of these men.

In World War II, millions of volunteers lined up enlist in the armed services to fight. I got kind of gauzily sentimental yesterday as I thought about them all, along with the men on Bataan. They volunteered from a sense of obligation. They did not belabor the idea of sacrifice. They did not question that they were fighting to defend this country, this way of life. However they had felt before Pearl Harbor, most volunteered without question once the war began. However you may feel about war, nationalism and patriotism, they went willingly. Many fought, many died, many came home permanently scarred. Black soldiers fought to defend a country that did not treat them equally. Nisei - Japanese Americans - fought to demonstrate their allegiance to a country that had put their families in camps. They all fought under the same flag.

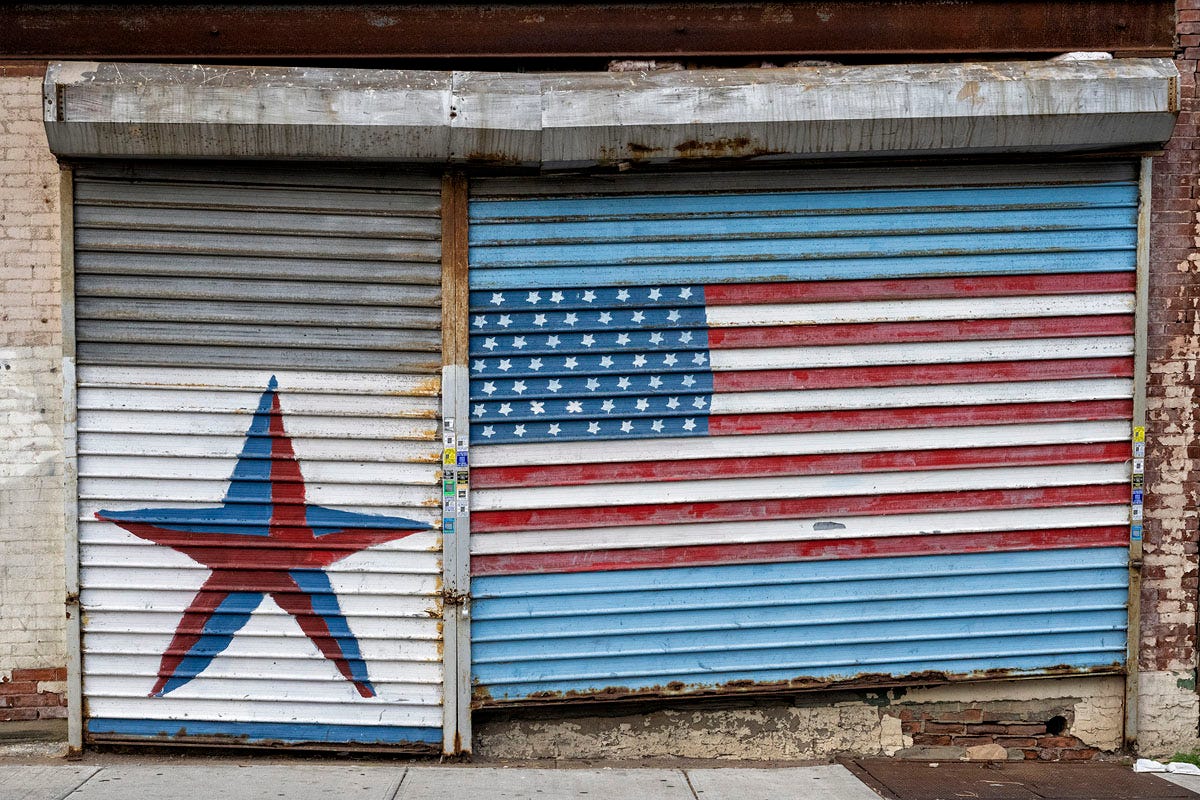

I like to photograph American flags that people paint on things, flags that adorn things, vernacular versions of the flag. Painting the flag on a wall is a statement. It may be a simple statement, but it meant something to the person who painted it. The person who painted the flag on their garage door was sending a message, signaling where they stood or doing it for themselves, maybe as a reminder of something. I would not know what that is, but they were saying something.

The flag still means something to most of us. Our national anthem—a notoriously difficult song to sing and a song that was not really chosen to be the anthem until the 20th Century—is about the flag. The flag that flew at Fort McHenry during that battle was preserved and is treated like a sacred relic. There are strict rules about how the flag must be flown and displayed. The coffins of dead soldiers are still draped in it. On the Fourth of July every year, millions of small flags appear to adorn the main streets of small towns across America. Art has been made using the flag and protests around the world borrow its symbolism. It’s a potent symbol because it means America. Everything about America.

The U.S. flag has had nicknames—“Old Glory,” “The Stars and Stripes” and others. It has been flown, revered, co-opted and burned. When someone wants to appeal to the virus of blind nationalism, we say that person is “draping themselves in the flag.” Flag burners are often reviled—but protected under the Constitution—and “flag wavers” are often reviled for different reasons. Everybody wants the flag to mean what they want it to mean. Everybody wants to define the symbolism. I wonder if people are aware of the concept of symbolism anymore? Maybe people just believe what they believe without questioning it.

Things are not always clear as you get older. I might worry if everything suddenly made sense. When I began to read and love history, my thinking about the past changed and my opinions expanded. They became ambiguous. But confusion and moral ambiguity are not a crime. And sometimes you can only figure things out in hindsight. In the meantime, all I can do is remember and live today. And honor the dead.

We hope you’re enjoying JUKE. Subscribe for free to receive new posts by email. To receive special member-only posts and benefits, please consider supporting our writers with a monthly or yearly paid subscription.

Paul Vlachos is a writer, photographer and filmmaker. He was born in New York City, where he currently lives. He is the author of “The Space Age Now,” released in 2020, “Breaking Gravity,” in 2021, and the just-released “Exit Culture.”

Everything about this is beautiful & thought-provoking. The merging of the historical with the personal is one of Paul's many strong points. Elegant!