Snapshots from the Dead Web

The internet is growing faster than it decays, but what’s lost is lost forever.

I have been wanting to do something for Juke’s “Dead Wood” column for a while. I had a few ideas and I won’t list them here as they are trade secrets and will remain in the deep vault until or unless I drag them out one day. The one that tugs at me the most, though, and which our illustrious Editor-In-Chief, T.M., has green-lighted, consists of digital detritus - the remains and fragments from the early days of the commercial World Wide Web. It was less than thirty years ago, but the birth of the Web shattered time, space and reality, so this stuff certainly qualifies as dead wood. Hell, some of it is even fossilized.

In 1995, I joined AOL - mainly because my new computer came with a modem and I figured that I had to use it. There was a CD-ROM for America Online in the box. AOL gave me a glimpse of what it meant to jump from the three-dimensional world to a virtual place online. At the same time, I heard about this thing called “the web,” mainly from some geeks and artist types I went to coffeehouses with in lower Manhattan. I found a local provider - Public Access Networks, aka “panix.com” - figured out the necessary software bits to negotiate point-to-point protocol, downloaded a browser, either Netscape or Mosaic, and then dialed in.

The modem made its squealing, soon-to-be-familiar sound of two boxes trying to talk with each other - modulation and de-modulation, whence the name “modem” - and I was online! But what did that mean? I had gotten to this place, but did not know where to go or what to do. There was little guidance at that time, although I had read articles. Articles in actual print magazines. People published lists of links. I don’t remember where I went first in what was then called either “web surfing” or, more ponderously, “cruising the information superhighway.” There was so much promise, though! Here was a fire hose of information and things to see. Vannevar Bush’s famed “Memex” information device had come to life.

I used webcrawler.com. A friend had told me about it. “You just go to that page and punch in what you’re looking for. It’ll pull up the results.” What did I look for? I don’t remember much about that first day. I was giddy that I had crossed the Rubicon and “gotten online.” I could report back to the guys in the diner that I had managed the connection. That was more important than whatever I found or did.

It was like traveling without leaving the house. All these years later, it still is in some ways. When I pull that phone out of my pocket and do whatever I do, whether it be shopping, socializing, or just entertainment, I'm leaving the corporeal plane. I'm not here anymore. I'm somewhere else, for better or for worse. So, something was compelling about it from the start, especially at that point in my life, when I was newly-single and living through a bad breakup. It was a welcome escape.

This “Dead Wood” contains some remnants from the early days of the web, some digital dead wood. “Remnants” may not be the best word. You can't find these if you look for them. Even if someone had left their late-1990s site live, eventually, they would have stopped paying for hosting or some code would be broken or another glitch would destroy it. Very few old web pages are live. And if people do find something, they’ll make fun of how crude it is. No worries, though, as nobody is looking. They’re too busy shopping or checking out porn.

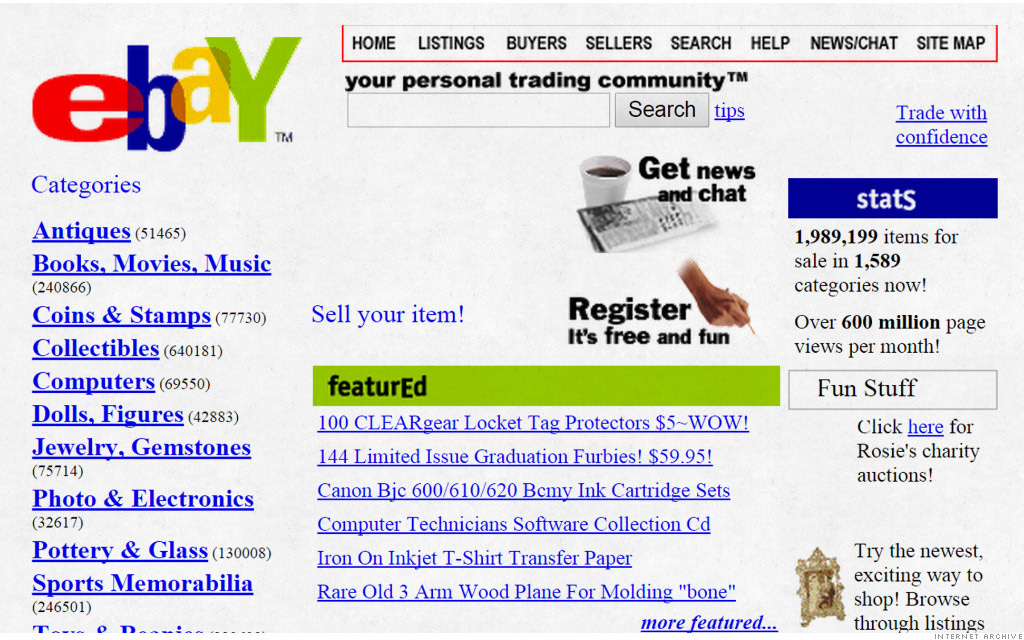

What little you can find of the early web is curated, like a museum collection. Most of that is over at archive.org’s “Wayback Machine.” They recognized early that the internet was dying as fast as it was growing and they took on the mission of preserving it, one snapshot at a time. They are an organization worth supporting if you enjoy history and culture. (http://wayback.archive.org) Most of what you’ll see here came from them. You can go there and get lost in a wondrous rabbit hole of ancient web pages, clunky user interface, and forgotten information. It's a time that feels as far away as ancient Egypt, but is still within living memory. These web pages are a window into what was and what was to come.

At that time, it was difficult to find breaking news online. The New York Times published a facsimile of their print front page, something called the “Cyber Times.” There was little in-depth reporting, and not much to buy in the early days. Online commerce needed to get a few technical ducks in order, which was happening quickly. I used to worry that someone would one day find a way to make money on the web, commercialize it and thereby ruin it. Little did I know that it was already too late. What I DID find in the mid-90s were some good astrology sites, early tech sites, forums and electronic bulletin boards for technical information on cars, guitars, cameras, and weather.

I can’t find the receipt for my first Amazon order, but I’m sure it was in 1995. I know it was a book. That’s all they seemed to sell then. And I thought it was pretty cool. I used a credit card. “Earth’s Biggest Bookstore.” I remember a lightbulb moment, maybe two years later, when I discovered that they had begun to sell all kinds of other crap besides books. This was also when I ditched Webcrawler for Altavista. At that time, it was all about what search engine you used. Google had not yet come along and, whenever a new search engine debuted, people would check it out and compare the results it brought back against their current favorite. I settled on Altavista.

Search engines came and went. News sites improved. The “information superhighway” morphed from a fun diversion to a place of business and connection. While I was busy taking long road trips, shooting strange photographs, playing in weird bands and having fun, other people were laser-focused on how to make money off this new resource, this almost accidental gift from the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency, known as DARPA. The initial research for a packet-based, distributed communication system began with them and was used by scientists for decades before being sprung on the world later on.

Even though eBay made money, the site felt like the spirit of the original web - a gigantic garage sale from all over the world. Just ten years later, when I was making a documentary on collectors, they were already referring to the “golden age of eBay,” a time when there was a lot of cool stuff that could be found for little money. They talked about a place that had not yet been discovered and ruined. Ten years in web time might as well be a millennium.

I first learned about Facebook in 2007, when I overheard it being discussed by college students I was teaching. It had been around for a while, but was not on my radar. I paid it little mind at first, but eventually checked it out. I lost countless hours of my life, answered the dumb prompts they used to get people to enter status updates, and posted photos. They were training their users to create content and become a product that could be sold to advertisers. None of us saw it that way at the time. When they changed the format from a “wall” to a timeline, around 2011, I was pissed off, but remained.

I signed up for Twitter in 2009, but did little with it except to cross-post photos from my website. It seemed like a frivolous site at first. If, in 2004, I had had the foresight and the money, I might have bought Twitter’s domain name, which was going for $4500 at the time. I had a student in one of my grad-school classes who was supporting himself by buying and then re-selling domain names, mainly for gay porn sites. He did well and might have been a commodities trader in another lifetime.

The internet is growing faster than it decays, but what’s being lost is being lost forever. There will be no trunk in the attic with dusty scrapbooks, no box on a stack in the subterranean floors of Harvard’s Widener Library, no re-issues on a bookstore shelf. What’s gone is gone. Those electrons will never be reanimated. That code is missing. All we have are screen shots, and they are not so secure, either. It was never meant to be a permanent medium, which is why it’s so precious now. The same will probably be true of the trillions of photos we take and then store in the cloud, along with the diaries, emails and other digital ephemera that we casually store, but rarely look at twice.

One day, we will stop paying the monthly storage fee. Or change accounts. Or forget to renew a credit card or a server will go down. It turns out that paper, magnetic tape and even celluloid have a better shot at immortality than a digital document. What’s gone is gone. Enjoy this now.

If you prefer to make a one-time donation, you can now contribute any amount to Juke using these Venmo and Paypal links.

Paul Vlachos is a writer, photographer and filmmaker. He was born in New York City, where he currently lives. He is the author of “The Space Age Now,” released in 2020, “Breaking Gravity,” in 2021, and the just-released “Exit Culture.”