Payphones

I may just be mourning the 20th century, the place I can never return to.

I cannot pinpoint the exact moment when the payphone became ancient history, when it became obsolete and antique. It was clearly not a moment at all, but it happened over the past 20 years and it felt as though it happened overnight. One day, they were a part of my life and the next day, no more. Maybe it was the day I finally got a cellphone with a reasonable plan. It happened in the 21st century. That much I do know.

I also can’t remember the first time I used a payphone, but it was probably not during the first 10 years of my life. Initially, I was not tall enough to reach one. In addition, I never went anywhere on my own. My guess is that I was in my early teens the first time I made a call from a payphone by myself.

For many decades, a payphone was the only way to contact somebody if you were away from home, whether you were at the store or on a trip. They were an integral, embedded part of life in the mid-to-late 20th century. By the 21st century, they experienced a mass and near universal extinction.

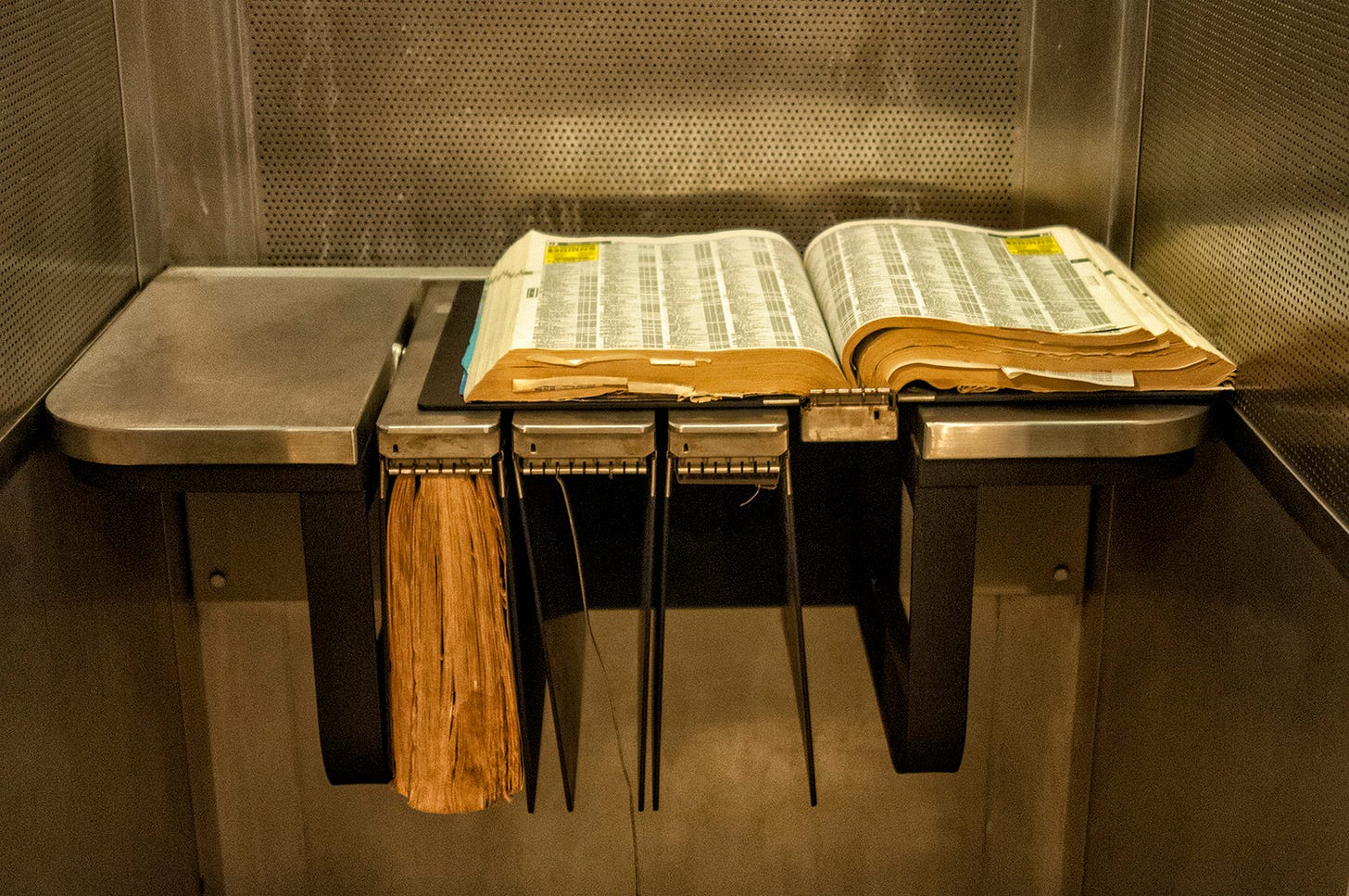

When I was young, fully enclosed phone booths were the norm. You would walk in and pull the handle to close the accordion-style door behind you. There was little room to turn around. The phone would be at chest level and there would usually be a stainless steel shelf below it, under which you might find a phone book that you could swing up to rest on the shelf.

If my mom was shopping at the store and I had to wait around, I would climb into the booth and shut the phone booth door, at which point a light and a small fan would turn on. It was an elegant, civilized experience and it provided some privacy – both for the caller and for any passersby, who did not have to hear whatever you were spouting on the telephone call. All parties were insulated and protected. Some phone booths, especially those in nicer hotels and restaurants, had a stool built in that you could sit on. In the older hotels, the booths were often built into the wall and constructed of fine, finished wood.

In the earliest days, when the telephone consisted of two pieces – an earpiece that you held to your ear and a microphone that you stood in front of – you had to put your face into the phone. Once phones were standardized with a combined handset, you could sit down and hold the phone against your head.

The earliest payphone I remember had three slots at the top for coins – one each for nickels, dimes and quarters. You could make local calls this way, but you had to call the operator for long distance, which one rarely did. There were usually instructions posted behind a piece of plastic on the front of the phone. These were along the lines of “Pick up receiver, wait for dial tone, deposit ten cents, dial your number.” They might then tell you how to make a long-distance call or how to get operator assistance.

Once I could reasonably pass as an adult – something I’m still working on, by the way – I went forth into the world and would use a payphone to call home from places such as Grand Central Terminal, various points around New York City and the video game arcade near my house in Yonkers. My reasons to use a payphone were few – to tell my parents I was going to be late, to coordinate with a friend about meeting somewhere and, once I got older, maybe to get laid.

If I had a date with someone, we set a time and a place and then just arrived and waited for the other person. It’s what everybody did. We had no choice. I suppose that, if things were critical, you could tell someone to call a mutually-agreed upon number and leave a message with someone. You could then call in to them and the would then pass on the information to you. In reality, that did not happen much.

Once I got older and began to travel more, I found myself pulling into strange gas stations or parking lots that had a payphone, then calling home to stay in touch or calling ahead for reservations and information. Non-local phone calls were expensive, so you could never have enough change. This is where calling cards came in handy. The phone companies issued plastic cards, but all you really needed were the code numbers, and then you could dial a long sequence, wait a moment, dial in some more numbers and establish a connection with someone far away, using no change at all. This was useful for calling motels or other businesses. If you were calling home or a friend, you could dial collect or “reverse the charges,” which simply meant that the person you were calling would be billed for your call. This could also get expensive.

Calling from the road was almost like sending a postcard. Since a long distance call on a payphone was less common than rattling away on your cellphone, it carried more weight. People would say, “where are you?” and I would respond with things like “I’m standing at a crossroads in Bentonia, Mississippi” or “I’m at a gas station in Death Valley” and then describe what I saw there.

It may sound banal now, even naive, but it felt special at the time. A phone call was more of a precious thing then. And we did not end every communication with the throwaway “love you,” tossed in as casually as “hello” or “goodbye.” Voices traveled over copper wires. You stood at the phone – you had to, of course – and held that handset to your face and spoke with purpose. Or you dissembled and mumbled idiocies about nothing, but you did it with purpose, damn it! You had to stop and find that phone and pay for that call. You had to remember the number or pull out an address book and dial it, one digit at a time. It took more effort to make a phone call from a payphone.

Maybe I have become a scrooge. What’s wrong with a good throwaway “love you”? I don’t know. In fact, I’m pretty sure that people don’t make a lot of phone calls these days. I see younger people on the street and, more often than not, they are holding their phone in front of them, screaming loudly into the ether on a video call with a friend. I wouldn’t mind so much if I didn’t have to unwillingly share their telephonic communion.

That was another great thing about phone booths – you could walk around them, avoid them. Now, we have to hear the dumb things that people say to each other whether we like it or not. Technology is dictating the evolution of human communication and it’s seeping into our lives in terrible ways. I don’t like ubiquitous connection and constant contact. There was a lot to be said for wandering the planet without being available continuously. We got to be alone with ourselves, something that has become a scarce commodity.

Much drama unfolded at the public payphone.

Trysts were arranged. Love affairs ended. Births and deaths were announced. Forgiveness was asked for and sometimes given. People were written off or given second chances. I was once left howling in the wind after being dumped while standing at a payphone on a lonely intersection. A text would have been more merciful in that case, but texting was not even a concept in the mid 1990s. So you were often standing there, emotionally naked, clutching a hard plastic receiver that was attached to a steel phone by an armored, coiled cable.

The phones had to be tough because they were often abused. Many times, I witnessed someone at the end of their rope on one side of a bad phone call, smashing the receiver against the phone. Smashing, smashing, smashing. The phones in all but the finest locations had scars. It was very difficult to break one of those plastic handsets, but it happened. I don’t know for certain, but I would wager that they swapped out the coin return lever for the ring that turned because it was less prone to being destroyed by an irate phone caller using the handset as a cudgel.

There was an element of danger, at least in the city, where you would sometimes hear a payphone ringing and, if you were really bored, you would pick it up to discover that someone was watching you from an unseen window and wanted to make a proposition. This was more common than you might think. On the highways and in the suburbs, you could pull up to a phone with an extra long cord and, as the sign enticed, “PHONE FROM YOUR CAR.”

You could make a phone call from payphone in the New York City subway system, where they were usually bolted to a steel support beam. When the trains came in, you had to either wait for them to stop or just hang up. And there were phones in other places – in school hallways, in the doorways of some restaurants, in government buildings and, of course, the massive banks of phones in Grand Central Terminal.

People down on their luck would routinely stick a finger in the coin return slot to see if there was some change. There often was. And people would use the phone booths for a moment of privacy or depravity. They became unofficial urinals or worse in New York City. By the 1990s, enclosed phone booths were a rare thing, replaced by the half units that gave you some protection from the elements and some sonic privacy, but left everything below your chest exposed. These half booths eventually became covered with paid advertising and, in fact, were still valuable for their ad space long after they stopped being useful or profitable as telephones. The big phone companies slowly divested of the booths. Too much trouble to maintain once cellphones came along.

Most people now would not touch a payphone. They’re filthy, although probably not as filthy as people think. I’m wondering if everyone under 50 is more of a germaphobe than their elders. Cash is dirty, payphones are dirty, door knobs are dirty. People carry antiseptic wipes and use them religiously. People don’t use water fountains or paper cups anymore, but disposable bottles or personal water bottles that they clean with dedicated, personal bottle brushes. We have gotten precious, less egalitarian and more narrowly focused on ourselves. There was something democratizing about waiting to use a payphone while some idiot was blabbing away and you had to signal how impatient you were. There was, at least, some human contact, another thing that has become sanitized and unfit to engage in. A payphone does not fit into personal bubbles.

Most of them don’t function now. In fact, I doubt that really young people would know how to work one. You have to pick up the handset and listen for a dial tone. That’s an alien concept to anyone under the age of 30. And if you were to find a phone with a rotary dial, which was common enough into the 1980s and even later in more rural areas, would a young person know how to use it?

What’s really shocking is how fast the payphone became obsolete. You could argue that the triumph of cellphones is technological Darwinism. Of COURSE they replaced the payphone – they’re more convenient, you can carry one around, they are cleaner, they are probably cheaper, and I could list many more reasons. This is a no-brainer. I can’t even make a contrarian, nostalgic, romantic argument for the payphone over a cellphone. It’s just the march of progress.

“Progress” is the word, isn’t it? We don’t talk about “progress” as much as we used to. We don’t focus on the manifest destiny of technology anymore. So much has happened at such a crazy pace. We are not thinking so much about how great “the future” will be. We have not caught up psychologically with technology. And I won’t even mention the internet. I should write a book about that. Actually, I did, although the story is mixed in with other things.

I should probably focus on my role as a witness to the technological tsunami that has taken place in the 60 years since I was born. I could say that I lived during the golden age of the payphone. So what? That and $2.75 will get me on the subway. The subway, by the way, was fifteen cents when I was a kid. Oh no, there I go again.

I could simply be mourning the loss of my true home – the 20th century, the place I can never return to. Maybe I don’t miss the payphone as much as the phone booth, that little oasis in the maelstrom. That tiny bit of private space in public. Where do we get that anymore? The spaces we create now are more virtual than real. We wall off the physical world with headphones and we plunge into the two-dimensional screen. We find connection electronically. Of course, that was the whole point of a phone call – “Reach out and touch someone” was an AT&T ad campaign from the late 1980s, which sounds like a long time ago.

The internet was less than ten years away from that campaign. Ubiquitous cellphones were a bit more than ten years away, but the focus was on the phone when it came to remote connection with another human. The telephone, though derided now by some younger people, was magical for decades as a way to connect with someone. Humans always strive to improve that impulse to connect. Letters were all we had for hundreds of years. Telegrams were something, but they were expensive and too brief. They also had to go through many hands and could not be truly private. They were mediated.

Telephones gave us the ability to send the human voice directly from one person to another. That’s a powerful thing. And the payphone allowed us to do that from public places, remote places, strange places. Our physical relationship with the phone – whether it was bolted to the wall or inside a booth or a half-booth – was almost an afterthought to everyone but the people who designed these things. We were “on the phone,” not “in a booth.”

We have some semblance of intimacy through short video chats with friends and family, but is that really intimate? The definition of intimacy may have changed. And intimacy may be less valued now than before. Do things such as love, alienation and joy change with the times? Are they just cultural values that always evolve? And where do we find refuge? How do we find refuge?

I am laying a lot more onto the poor phone booth than its designers ever intended. But I am overlaying it with my own experience. I spent many hours talking to people from a payphone. Somehow, time stood still and the outer world faded a bit while I stood there, talking on the phone. The phone system might ask for more money during the call, sirens might be rolling by, and the world did not actually stop, but nothing mattered as much as the connection on that phone line. Talking on a cell is not that different. We walk around while doing it or we carve out a space and talk from there. Why does it feel different to me?

I don’t know, but it’s not the same.

All photos by Paul Vlachos.

This piece appeared in EXIT CULTURE: WORDS AND PHOTOS FROM THE OPEN ROAD. You can purchase the book on Amazon HERE.

If you enjoyed this post, hit the ♡ to let us know.

If it gave you any thoughts, please leave a comment.

If you think others would enjoy it, hit re-stack or share:

If you’d like to read more:

And if you’d like to help create more Juke, upgrade to a paid subscription (same button above). Otherwise, you can always help with a one-time donation via Paypal or Venmo.

Those half-booths made it very difficult for Clark Kent to change his clothes, too.

oh what a walk down memory lane. those booths represent another time, another reality and a time when we were able to be alone with ourselves naturally. loved reading this, Paul. thank you