Once Upon a Time

I have some stories I need to tell...

Did you ever see “Broadway Danny Rose?” It’s a Woody Allen film from 1984 and it starts out in the old Carnegie Deli in New York City. A bunch of comedians are hanging out and talking shop, swapping stories. They start to talk about an eccentric personal manager they all know, Broadway Danny Rose. After some small talk and a story or two, one of them shushes everybody and says, “Okay, are you ready, because I have the greatest Danny Rose story,” and he tells them all to settle in, which they do and which all of us who are watching the movie do. We settle in with some measure of anticipation and a little tingle because we know it’s going to be good, it’s going to be diverting and it’s going to fill us with something. Some ineffable satisfaction. This story will transport us. To where? That depends on the viewer, but it will take you somewhere else, somewhere beyond this pale moment.

That’s what real life is like, as well. I was part of a conversation recently between Tonya and a woman who had been married to a painter. He had been part of an art movement that stretched from the 1950s to the 1990s. He knew many artists and writers from that time and some of them were almost mythical figures. They became more famous with each passing year since their deaths. But they were all dead now, including her husband, and she referred to herself as “the holder of the stories.” She has a full life and is a successful artist in her own right, but this is one role she fills, not always happily - the holder of the stories.

I have seen this with Tonya. She was married to a lesser figure, someone who was part of a scene, as well. He collected stories and became a bit notorious for his own work as a journalist. She is now the holder of his stories, the ones she saw and the ones he told her.

Stories are one of the things that make us human. It is possible that - somewhere - dogs or crows or lions sit around and communicate with each other about their ancestors in some tongue that we could never understand. It is possible, but not likely. Animals are too much in the moment to think about their past. They have no way to record history - another trait unique to humans and one that goes back to ancient times, before writing.

The earliest medium for recording stories was cave art. Before that, people simply re-told the tales that had shaped them and their cultures. They sat around and told stories. The best of them were the holders of the stories. This job is rarely lucrative - it’s often not even a job, but more of a sacred role. Some writers in western civilization over the past two hundred years have found a way to make money off of it, but there is no guarantee you can make a living that way. Storytellers are born, not made.

We tell stories to remember what happened, to entertain, to enlighten. Sometimes, we tell them so that we can forget - you get the story and then you can file it away. You can shape it. Churchill famously said, “I know what the history books will say because I will write them.” And he did. Some people swap stories. Careers are built by those who modify stories - the revisionists. There are those who study stories - historians. And then there are those who sit back contentedly and just listen, let themselves be transported, and re-live what happened long ago. Or not so long ago.

Of course, the idea is to live one’s life fully, to create one’s own story, to be in the moment. Not everybody can write it down, not everybody can gather old stories up like wheat, transmute them and then feed them to other people. Not everybody could or should do that. But the holder of the stories is as important a role as those who gather the wheat or those who fix cars or those who care for others. You can’t eat a story. It won’t transport you like a car and it won’t necessarily heal your body, but a story is salve for the soul, fodder for the mind, and a distraction from the pain of existence. A story gives us hope, informs us and teaches us.

I have a list of stories that I need to tell. When I remember something now, I’ll write it down, make a note, and hope to circle back later and flesh it out. Sometimes, a friend of mine - also a story collector - will tell me, “You should write about that time you were on that TV show Wonderama and they gave you the Suzy Homemaker oven because the girl chose the boys’ prize.” The list of stories I need to finish gets longer every year. Isaac Babel, that most incredible storyteller, was supposed to have said, “LET ME FINISH MY WORK” just before Stalin’s henchmen executed him. We carry them around. Of course, they’re not all interesting. Some stories are better left untold, maybe forgotten. Either way, they occupy space.

Tonya and I went on a trip this summer, a road trip where we sat next to each other for all of the daylight hours, every day. We talked a lot. This is one of the most intimate forms of transportation, whether you do it alone and talk with yourself or with another person. We told stories, although most of them came up in between conversations about logistics - When do we stop? What do we eat? Where will we go? - we remembered things. “I knew this guy….” or “When I was 20…” or “This is what he used to say to me…” Little stories all day.

We went on a trip for the sake of leaving home so that we could return, something like “The Odyssey,” another seminal set of stories. And we had a few things to do on this trip. One of them was to clear out a cabin, a cabin filled with the detritus of a life that verged on hoarding, but there was some fairy dust sprinkled on this cabin by one of these famous literary figures. Fairy dust and then mouse droppings. They co-existed equally on different planes in the same location.

We began the trip with some trepidation, as the hound was still recovering from his back injury and we were trying to find a way to travel and protect him from the rigors of the road, namely high motel beds that he can no longer leap from. As with most road trips that originate in the East, the first few days consisted of locking ourselves in the space capsule and grinding out the miles. We gutted it out through Pennsylvania and Ohio. We ate out of the cooler because we have both had our share of bad road food over the years. Then it was the middle states, as we pushed on towards Kansas, where we planned to see some friends.

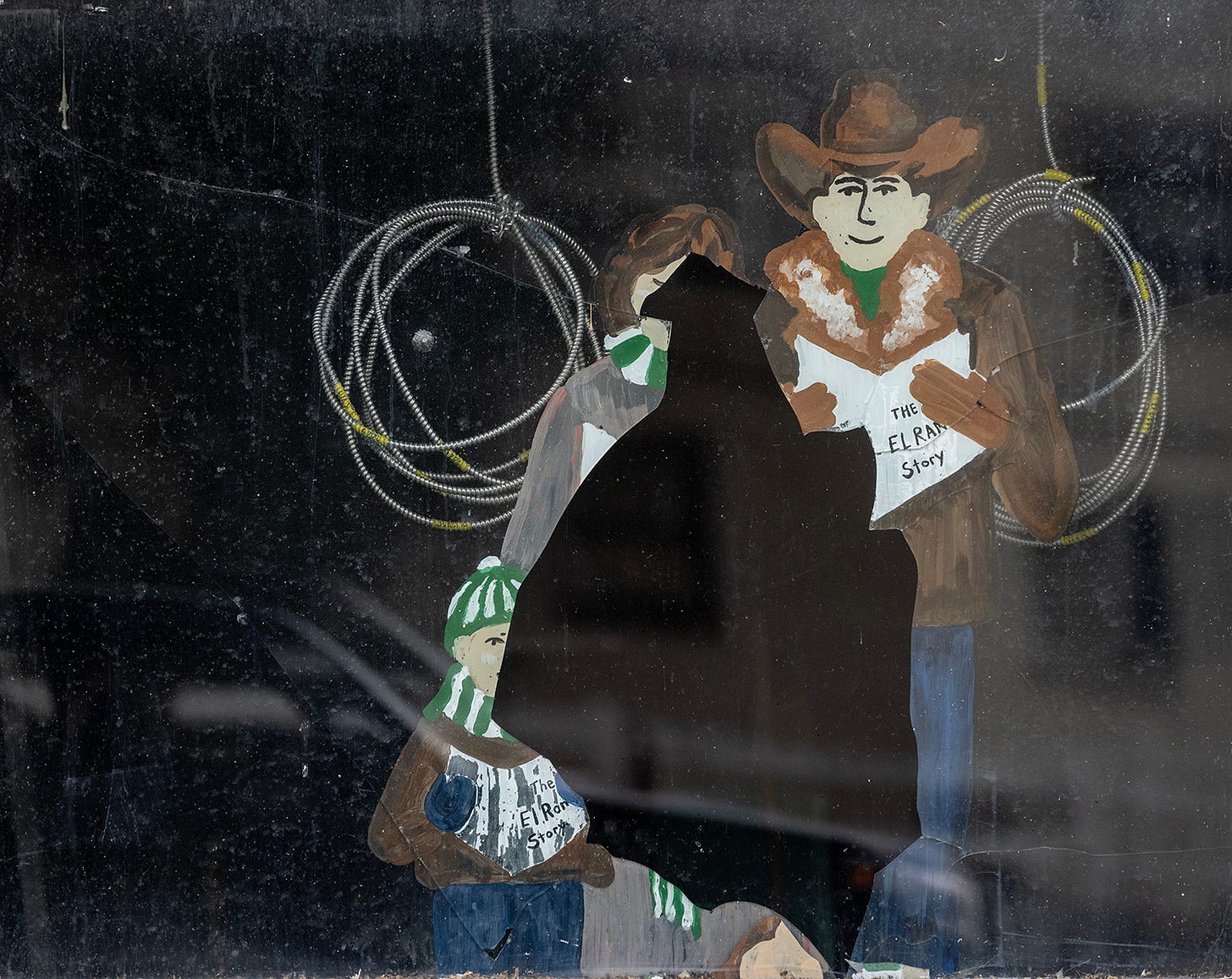

I have come to appreciate Kansas, a state I used to just blow through. Now that I know actual humans there and drive the federal and state highways, not the Interstates, it’s a different place for me. When you slow down and hit the smaller towns or linger in the cities, the real contours take shape. It’s possible to walk in the daily life of a place, rather than simply fly through on a concrete runway. We took photos, we hung out, we woke up on the third day in Olathe and aimed for Guymon, Oklahoma, a short haul from the eastern edge of New Mexico, where we planned to hunker down for a few days. As always, when we crossed the state line into New Mexico, it felt special. I can’t say why. It could be a combination of the light, the food, the people, the expectation of magic, the actual west. Or maybe it’s just straight-up magic. We have both - separately - loved New Mexico for a long time.

We visited some land in the south and then hung out in Carrizozo and Socorro. We went through a string of hamlets on the way to Gallup, then landed in Albuquerque. This took a few days. After ABQ, we went up to Santa Fe and discovered that neither of us hated that town as much as we had thought we did. We found some good, locally-made dog treats and lots of breakfast burritos, then headed north so that Tonya could have lunch with her friend, the painter. I was going to say “the painter’s wife,” but she’s a painter in her own right. She does hold his stories, though, and that’s where this meandering piece began, talking about the holders of the stories.

When we left her, we went into Colorado so that we could be at the cabin the next day. Before I forget, let me say that we had a lot of fun, even though we were moving fast. We cleared that cabin of a lifetime’s worth of detritus and weird juju. I touched a beam that looked out of place and she explained, “He needed to shore this up.” She told me the story of the leaks, how he built the place and where he was in his life at the time. It is endless, the collection of memories. For better or worse, she holds his stories. That's what we do. There were stories in this cabin and Tonya holds many of them.

We cleared it out, burned a bunch of sage and Palo Santo, and then we threw those mouse droppings to the wind. I whooped it up a bit and danced around on the porch and, by the time we left - and left it in the hands of the people who were going to sell it - we had lightened our own psychic load and were ready to move on. Because, sometimes, stories can weigh you down. You don’t have to forget them - and maybe you can’t forget them - but you can put them on the shelf for a while, you can send them out the window, you can put them in a box. And then you can work on new ones. That’s what we did.

We aimed the nose of our craft west and headed across Nevada. We hooked up with a friend of mine and soaked our collective butts in hot springs, told each other a few tall tales, and went over the hill, the Sierra Nevadas, towards San Francisco. We stopped along the way and saw Tonya’s mom, who holds a bunch of her own stories, as well. All parents do. They are the witnesses. And it makes me wish I had gotten more of the stories out of my own mom and dad before they died. I heard plenty of them. They were a part of my growing up, and my brother and I sometimes trade these stories. It’s a way to remember, to go back and visit the ancient ones and our own childhoods. I’m grateful that I have enough good ones to enjoy. It’s not like that for everyone.

My dad used to tell me about his childhood on the rough streets of Inwood, at the upper tip of Manhattan. They were a poor family to begin with and he turned 7 as the Great Depression hit. He had crazy stories of what he did when he was a kid, although he wasn’t always in the mood to tell them. In the early 2000s, I was riding my bike around the island, as I like to do, and he called me. I always picked up for my dad. He asked where I was and I described the area by the Harlem River Drive, the bike path near the old aqueduct and the other two bridges. He got quiet for a moment, then said, “I got jumped there when I was about 7 years old. Some kids took my roller skates.” I marveled that he was so far from home, by himself, at that age. I commiserated with him. The memory still seemed fresh. We talked about it and then I went on my way. He may not have told that story for over 70 years. And now I am the only one left who knows it. Except for you.

My childhood is a big pile of stories. Some people share them with me - friends and family. Whoever lives the longest is the keeper of the stories. When I was a teenager and smoking a lot of weed, my once-great memory developed some holes. A friend would say to me, “Remember when we did such and such a thing last summer?” and I would blink. He had those tales. Maybe I was living too fast to remember, maybe it was the drugs, but that became a theme. When my friend Paul told me, “You were at my wedding,” I said, “Really?” He looked incredulous and said, “I have the photos.”

Stories live on tape, on video, on paper - all transitory, but less tenuous than that most ethereal medium - memory. Which is why we inscribe our names and dates in stone at the graveyard, a vain attempt to stave off eternity. I gathered stories growing up. It was not something I set out to do, but there were times when I was the only witness. Friendships, collaborations, projects - each had stories and I have some of them. Every marriage or relationship, likewise, is a private affair, with private stories. While I don’t remember everything, I remember enough from the 1980s. Some of those stories are not mine to tell. I can only hold them and try to remember. Or try to forget.

People told me things before they died. Why do people tell you things in private? So they don’t bear the burden of holding those things alone? I don’t know. Again, some things are not mine to repeat. I am thinking now about memory. “Do you remember when we used to climb to the top of Memorial Hall, in Cambridge, before they rebuilt the tower that burnt down?” “How about that time we stood at the edge of Abingdon Square Park and talked about how you were going blind?” “That crazy time we got picked up hitchhiking by those two thugs with a bong on I-95?” “What did we talk about on those long bike rides?” “When was the last time you saw him?” “We carried his suitcase across town, what did he say?” It goes on forever. If you live long enough - and, hopefully, hard enough - you’ll see and hear and do things. These are your stories.

When I think back to my childhood in Yonkers, some stories come to mind more quickly than others. It feels like scrubbing through a video and slowing down for the highlights, the greatest hits - the texture of the living room carpet that I crawled on, being carried around by my dad in the pre-dawn, getting in trouble with the neighbors when we started to play electric guitars, getting caught shoplifting at the supermarket when I was 13. Some of these are just snapshots. Some have beginnings, middles and ends.

I remember the time, after we moved to Princeton, New Jersey, when I got detained by the police at the age of 11. I was lonely in Princeton, having been ripped away from my friends and my familiar dead-end street in Yonkers. I read a lot, rode my bike a lot, and fell in with a couple of other alienated kids. I had gone with one of them a mile away to a Unitarian Church with an A-frame roof that came down to the ground. We tried to climb it, as young boys do, got halfway to the top, and realized there was no way to go on, so we slid back down and walked away slowly, lost in adolescence and plotting our next dumb adventure. I had a tiny piece of shingle in my hand that I picked up off the ground just before the police car screamed up. The cops stopped us and I dropped that scrap of shingle on the ground. They accused us of vandalizing the church and took us into the precinct. We were so little. We were terrified. They called our parents and my mom came to get me. The dinner table that night was not fun.

Some people tell their stories to others, but some of us write them down. We collect them. It’s all I really have, my stories. Those of us who tell stories have no choice. Some conjure them from the ether and that’s called fiction. Others gather them from the dust of experience. The trick is remembering. Some people are blessed or cursed with a good memory. I’m usually too focused on what’s in front of me to store the facts. If I don’t write things down, I’ll forget. It’s some hyper-focus disease. I’m sure that, if I were young now, I’d be diagnosed with ADHD. When I’m not completely in the moment, I’m trying to avoid the moment via worry and over-thinking. It sounds bad, but I think I’m okay. “Tell the story, Paul. Tell the story…” What’s the story here?

The story now is that we’re in the process of moving, of leaving Greenwich Village. We’re working on the next set of stories. My back hurts, my head hurts, my hands hurt. I have spent the past year, it seems, carrying heavy boxes of books - a million human-years’ worth of stories - from one storage space to another, from that cabin in Utah to a truck, from my shelves to New Jersey, from a house in Kansas to a storage unit in Wichita, then to a van. Who knows where they will all end up?

Maybe some of these storytellers who wrote books lied to us. They did what they had to do. Once a story is released, it’s a creature on its own. You let it go and you never know what a story will do once it’s out there in the wild, moving from person to person, place to place. There are those who steal stories. That can be a form of flattery, but it can also be plagiarism. And then we have the tech parasites who steal the libraries of the world, dump them into their hoppers and generate garbage. “AI” may have its place, but AI cannot tell a story of its own because it hasn’t lived. It can only repeat what it’s been fed.

We have to live with our own stories. We don’t have to repeat them to others. For those of us who do, though, it’s a sacred calling. This storytelling is not always selfless, but it is often holy. We move swiftly through the chasm of life and grasp at moments along the way. We remember and then repeat fragments to other humans in the quest for connection. Every painting - even the abstract ones - every sculpture, every song is a story. Every photograph is a story, as well. We just fill in the blanks in our heads. Half the time, when the phone rings and I pick it up, I’m expecting a story.

Back in Utah, after the cabin, we huddled in a dog pile on an inflatable mattress on the floor of a motel. Earlier, we had pulled a dead, decomposed deer from the rutted driveway. He had been dead for a while and was half hollowed-out and desiccated. He still stank. Santo the hound was transported by this smell. We dragged this dead deer by his antlers, then moved a mountain of stuff, the pieces of a life. We collapsed later in the motel - I, the woman and the small dog. We were on that uncomfortable blow-up mattress to protect his back. He injured himself jumping off a motel bed last year, but that’s another story and not for here. We lay together to stay warm. And that’s why we tell each other stories - to stay warm, to protect the pack, to protect ourselves, to get through another day and, hopefully, another night on this planet.

Paul Vlachos is a writer, photographer and filmmaker. He was born in New York City, where he currently lives. He is the author of “The Space Age Now,” released in 2020, “Breaking Gravity” in 2021, and 2023’s “Exit Culture.”

If you enjoyed this post, hit the ♡ to let us know.

If it gave you any thoughts, please leave a comment.

If you think others would enjoy it, hit re-stack or share:

If you’d like to read more:

And if you’d like to help create more Juke, upgrade to a paid subscription (same button above). Otherwise, you can always help with a one-time donation via Paypal or Venmo.

Excellent article that makes me rethink everything about how story has defined me. How poems have taken the place of novels or short stories. How the wrong tangent in genealogy research collected stories I love about people I AM NOT RELATED TO. Who the F cares. It's amazing how many people have written and told their stories in letters, journals, and O.M.G. obits. What a treasure trove are the obits. And your mention of inscribing our names and dates on stones. Who lies here? Thank you, Paul, for another great piece of writing. And I'm glad you both are getting close to the end of one grizzly chapter and starting a brilliant new one. Pet little Santo for me and hug Tonya.

For someone like you Paul, who enjoys telling stories, I have to add that you are a very good listener, too. Colorist, architect, film maker, etc. All listening acts, too. With Juke, we all share our affinity there. Words are landscapes, I believe. Why, I, too, loved this piece, Paul.

Aside from it taking me way back to times when I could not honestly share much. When speaking openly of my experiences was going too far. In college I chose to major in philosophy. Some students readily understood, while others, like me, found it so hard. I managed to graduate. Then, at an off campus party, I was locked at the kitchen sink doing dishes, when the head of our philosophy department arrived. She stood and stared at me. Like what are YOU doing here? She'd scared me to death before. Party-goers came and went while I dried plates, etc. The professor stopped the flow, and rather condescendingly, she asked me, "What did taking philosophy do for you, Miss Christopher?" I dried a glass, set it in the rack, and turned to her. I felt publically flunked. I am shy, and she knew it. I turned to face her. "Well, there is no book or magazine or newspaper, science article, or equation, any piece of writing, that I cannot read and understand if I set my mind to it." My first and last perfect story. Thank you for reminding me just how important storytelling is, Paul. Precious, despite the hardships, the hope in paying attention to the big and small things. All of it.