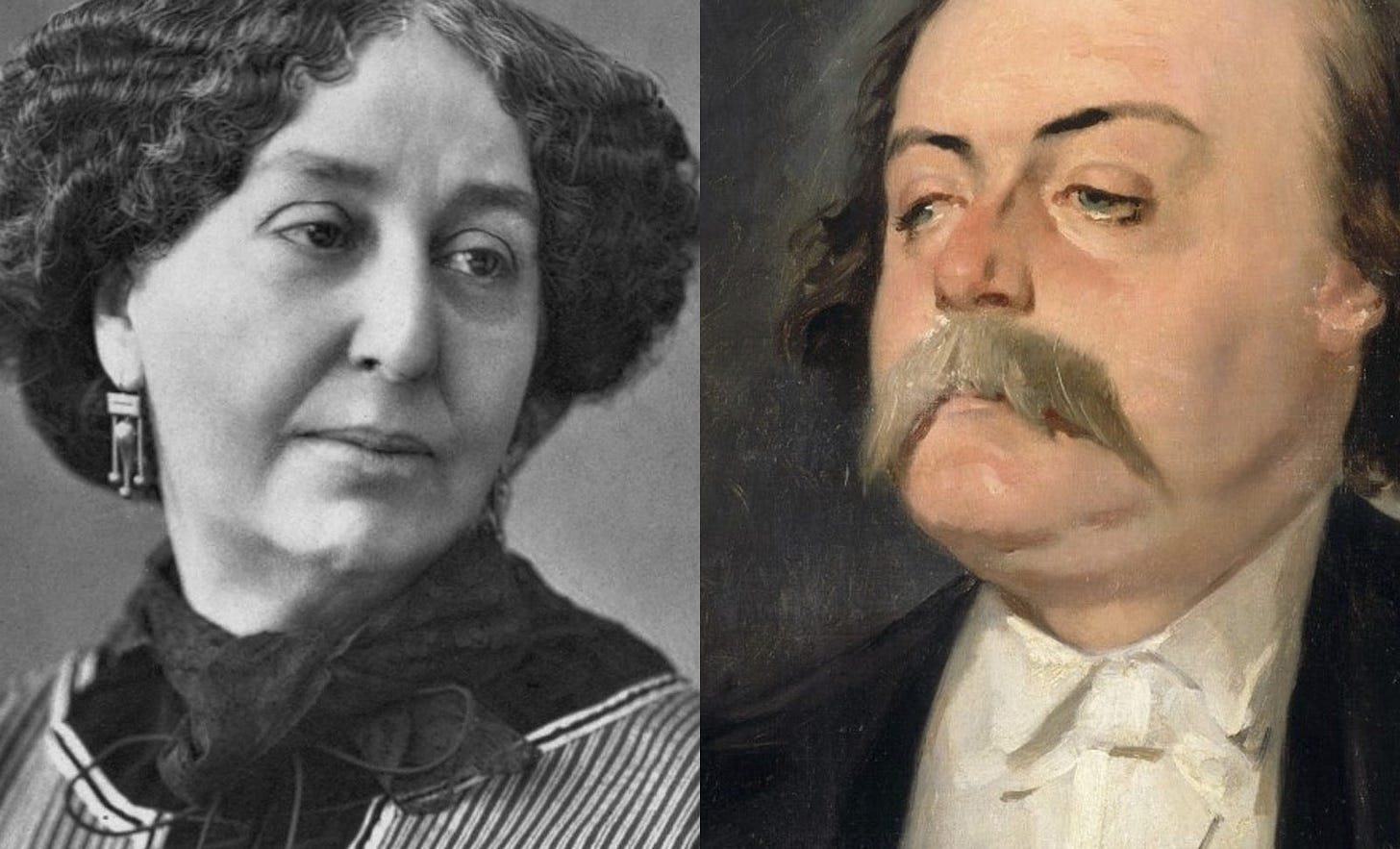

"I quite frankly like you:" the letters of George Sand and Gustave Flaubert

"I shall be here, working hard, but ready to run, and loving you with all my heart."

I love reading letters. Love letters. Thoughtful letters. Angry letters. They are often as intimate as a journal, but, as they’re meant to be read, they’re generally written with greater clarity. In letters, we try to be understood. Something about the page, and the confidante who will receive it, invites us to speak more truthfully. When we write a letter from the heart, we may lay ourselves open completely.

I want to share with you a few of the Sand-Flaubert letters today because I find them extraordinary. They are so immediate, these letters, written with vulnerability and thoughtfulness and wild shifts of mood and temperment. Though the two weren’t lovers, they write with such profound affection and sympathy to each other, even in their disputes about philosophy and art, I find myself moved by each word. Who wouldn’t want to be written to in this way?… TM

To George Sand

1863

Dear Madam,

I am not grateful to you for having performed what you call a duty. The goodness of your heart has touched me and your sympathy has made me proud. That is the whole of it.

Your letter which I have just received gives added value to your article and goes on still further, and I do not know what to say to you unless it be that I quite frankly like you.

It was certainly not I who sent you in September, a little flower in an envelope. But, strange to say, at the same time, I received in the same manner, a leaf of a tree.

As for your very cordial invitation, I am not answering yes or no, in true Norman fashion. Perhaps some day this summer I shall surprise you. For I have a great desire to see you and to talk with you.

It would be very delightful to have your portrait to hang on the wall in my study in the country where I often spend long months entirely alone. Is the request indiscreet? If not, a thousand thanks in advance. Take them with the others which I reiterate.

To Gustave Flaubert

Paris, 15 March, 1864

Dear Flaubert,

I don’t know whether you lent me or gave me M. Taine’s beautiful book. In the uncertainty I am returning it to you. Here I have had only the time to read a part of it, and at Nohant, I shall have only the time to scribble for Buloz; but when I return, in two months, I shall ask you again for this admirable work of which the scope is so lofty, so noble.

I am sorry not to have said adieu to you; but as I return soon, I hope that you will not have forgotten me and that you will let me read something of your own also.

You were so good and so sympathetic to me at the first performance of Villemer that I no longer admire only your admirable talent, I love you with all my heart.

George Sand

To Gustave Flaubert

Saint-Valéry, 26 August, 1866

Monday, 1 A. M.

Dear friend, I shall be in Rouen on Tuesday at 1 o’clock, I shall plan accordingly. Let me explore Rouen which I don’t know, or show it to me if you have the time. I embrace you. Tell your mother how much I appreciate and am touched, by the kind little line which she wrote to me.

G. Sand

To George Sand

Croisset, Saturday evening, 1866

Your sending the package of the two portraits made me think that you were in Paris, dear master, and I wrote you a letter which is waiting for you at rue des Feuillantines.

I have not found my article on the dolmens. But I have my manuscript (entire) of my trip in Brittany among my “unpublished works.” We shall have to gabble when you are here. Have courage.

I don’t experience, as you do, this feeling of a life which is beginning, the stupefaction of a newly commenced existence. It seems to me, on the contrary, that I have always lived! And I possess memories which go back to the Pharaohs. I see myself very clearly at different ages of history, practising different professions and in many sorts of fortune. My present personality is the result of my lost personalities. I have been a boatman on the Nile, a Jeno in Rome at the time of the Punic wars, then a Greek rhetorician in Subura where I was devoured by insects. I died during the Crusade from having eaten too many grapes on the Syrian shores, I have been a pirate, monk, mountebank and coachman. Perhaps also even emperor of the East? ?

Many things would be explained if we could know our real genealogy. For, since the elements which make a man are limited, should not the same combinations reproduce themselves? Thus heredity is a just principle which has been badly applied.

There is something in that word as in many others. Each one takes it by one end and no one understands the other. The science of psychology will remain where it lies, that is to say in shadows and folly, as long as it has no exact nomenclature, so long as it is allowed to use the same expression to signify the most diverse ideas. When they confuse categories, adieu, morale!

Don’t you really think that since ’89 they wander from the point? Instead of continuing along the highroad which was broad and beautiful, like a triumphal way, they stray off by little sidepaths and flounder in mud holes. Perhaps it would be wise for a little while to return to Holbach. Before admiring Proudhon, supposing one knew Turgot? But le Chic, that modern religion, what would become of it!

Opinions chic (or chiques): namely being pro-Catholicism (without believing a word of it) being pro-Slavery, being pro-the House of Austria, wearing mourning for Queen Amélie, admiring Orphée aux Enfers, being occupied with Agricultural Fairs, talking Sport, acting indifferent, being a fool up to the point of regretting the treaties of 1815. That is all that is the very newest.

Oh! You think that because I pass my life trying to make harmonious phrases, in avoiding assonanees, that I too have not my little judgments on the things of this world? Alas! Yes! and moreover I shall burst, enraged at not expressing them.

But a truce to joking, I should finally bore you.

The Bouilhet play will open the first part of November. Then in a month we shall see each other.

I embrace you very warmly, dear master.

To Gustave Flaubert, at Croisset

Nohant, Monday evening, 1 October, 1866

Dear friend,

Your letter was forwarded to me from Paris. It isn’t lost. I think too much of them to let any be lost. You don’t speak to me of the floods, therefore I think that the Seine did not commit any follies at your place and that the tulip tree did not get its roots wet. I feared lest you were anxious and I wondered if your bank was high enough to protect you. Here we have nothing of that sort to be afraid of; our streams are very wicked, but we are far from them.

You are happy in having such clear memories of other existences. Much imagination and learning—those are your memories; but if one does not recall anything distinct, one has a very lively feeling of one’s own renewal in eternity. I have a very amusing brother who often used to say “at the time when I was a dog....” He thought that he had become a man very recently. I think that I was vegetable or mineral. I am not always very sure of completely existing, and sometimes I think I feel a great fatigue accumulated from having lived too much. Anyhow, I do not know, and I could not, like you, say, “I possess the past.”

But then you believe that one does not really die, since one lives again? If you dare to say that to the Smart Set, you have courage and that is good. I have the courage which makes me pass for an imbecile, but I don’t risk anything; I am imbecile under so many other counts.

I shall be enchanted to have your written impression of Brittany, I did not see enough to talk about. But I sought a general impression and that has served me for reconstructing one or two pictures which I need. I shall read you that also, but it is still an unformed mass.

Why did your trip remain unpublished? You are very coy. You don’t find what you do worth being described. That is a mistake. All that issues from a master is instructive, and one should not fear to show one’s sketches and drawings. They are still far above the reader, and so many things are brought down to his level that the poor devil remains common. One ought to love common people more than oneself, are they not the real unfortunates of the world? Isn’t it the people without taste and without ideals who get bored, don’t enjoy anything and are useless? One has to allow oneself to be abused, laughed at, and misunderstood by them, that is inevitable. But don’t abandon them, and always throw them good bread, whether or not they prefer filth; when they are sated with dirt they will eat the bread; but if there is none, they will eat filth in secula seculorum.

I have heard you say, “I write for ten or twelve people only.” One says in conversation, many things which are the result of the impression of the moment; but you are not alone in saying that. It was the opinion of the Lundi or the thesis of that day. I protested inwardly. The twelve persons for whom you write, who appreciate you, are as good as you are or surpass you. You never had any need of reading the eleven others to be yourself. But, one writes for all the world, for all who need to be initiated; when one is not understood, one is resigned and recommences. When one is understood, one rejoices and continues. There lies the whole secret of our persevering labors and of our love of art. What is art without the hearts and minds on which one pours it? A sun which would not project rays and would give life to no one.

After reflecting on it, isn’t that your opinion? If you are convinced of that, you will never know disgust and lassitude, and if the present is sterile and ungrateful, if one loses all influence, all hold on the public, even in serving it to the best of one’s ability, there yet remains recourse to the future, which supports courage and effaces all the wounds of pride. A hundred times in life, the good that one does seems not to serve any immediate use; but it keeps up just the same the tradition of wishing well and doing well, without which all would perish.

Is it only since ’89 that people have been floundering? Didn’t they have to flounder in order to arrive at ’48 when they floundered much more, but so as to arrive at what should be? You must tell me how you mean that and I will read Turgot to please you. I don’t promise to go as far as Holbach, although he has some good points, the ruffian!

Summon me at the time of Bouilhet’s play. I shall be here, working hard, but ready to run, and loving you with all my heart. Now that I am no longer a woman, if the good God was just, I should become a man; I should have the physical strength and would say to you: “Come let’s go to Carthage or elsewhere.” But there, one who has neither sex nor strength, progresses towards childhood, and it is quite otherwhere that one is renewed; where? I shall know that before you do, and, if I can, I shall come back in a dream to tell you.

To Gustave Flaubert

Paris, 10 November, 1866

On reaching Paris I learn sad news. Last evening, while we were talking—and I think that we spoke of him day “before yesterday—my friend Charles Duveyrier died, a most tender heart and a most naive spirit. He is to be buried tomorrow. He was one year older than I am. My generation is passing bit by bit. Shall I survive it? I don’t ardently desire to, above all on these days of mourning and farewell. It is as God wills, provided He lets me always love in this world and in the next.

I keep a lively affection for the dead. But one loves the living differently. I give you the part of my heart that he had. That joined to what you have already, makes a large share. It seems to me that it consoles me to make that gift to you. From a literary point of view he was not a man of the first rank, one loved him for his goodness and spontaneity. Less occupied with affairs and philosophy, he would have had a charming talent. He left a pretty play, Michel Perrin.

I travelled half the way alone, thinking of you and your mother at Croisset and looking at the Seine, which thanks to you has become a friendly goddess. After that I had the society of an individual with two women, as ordinary, all of them, as the music at the pantomime the other day. Example: “I looked, the sun left an impression like two points in my eyes.” Husband: “That is called luminous points,” and so on for an hour without stopping.

I shall do all sorts of errands for the house, for I belong to it, do I not? I am going to sleep, quite worn out; I wept unrestrainedly all the evening, and I embrace you so much the more, dear friend. Love me more than before, because I am sad.

G. Sand

To George Sand

Monday night

You are sad, poor friend and dear master; it was you of whom I thought on learning of Duveyrier’s death. Since you loved him, I am sorry for you. That loss is added to others. How we keep these dead souls in our hearts. Each one of us carries within himself his necropolis.

I am entirely undone since your departure; it seems to me as if I had not seen you for ten years. My one subject of conversation with my mother is you, everyone here loves you. Under what star were you born, pray, to unite in your person such diverse qualities, so numerous and so rare?

I don’t know what sort of feeling I have for you, but I have a particular tenderness for you, and one I have never felt for anyone, up to now. We understood each other, didn’t we, that was good.

I especially missed you last evening at ten o’clock. There was a fire at my wood-seller’s. The sky was rose color and the Seine the color of gooseberry sirup. I worked at the engine for three hours and I came home as worn out as the Turk with the giraffe.

A newspaper in Rouen, le Nouvelliste, told of your visit to Rouen, so that Saturday after leaving you I met several bourgeois indignant at me for not exhibiting you. The best thing was said to me by a former sub-prefect: Ah! if we had known that she was. here... we would have... we would have...” he hunted five minutes for the word; “we would have smiled for her.” That would have been very little, would it not?

To “love you more” is hard for me—but I embrace you tenderly. Your letter of this morning, so melancholy, reached the bottom of my heart. We separated at the moment when many things were on the point of coming to our lips. All the doors between us two are not yet open. You inspire me with a great respect and I do not dare to question you.

To Gustave Flaubert

Palaiseau, 22 November, 1866

I think that it will bring me luck to say good evening to my dear comrade before starting to work.

I am quite alone in my little house. The gardener and his family live in the pavilion in the garden and we are the last house at the end of the village, quite isolated in the country, which is a ravishing oasis. Fields, woods, appletrees as in Normandy; not a great river with its steam whistles and infernal chain; a little stream which runs silently under the willows; a silence... ah! it seems to me that I am in the depths of the virgin forest: nothing speaks except the little jet of the spring which ceaselessly piles up diamonds in the moonlight. The flies sleeping in the corners of my room awaken at the warmth of my fire. They had installed themselves there to die, they come near the lamp, they are seized with a mad gaiety, they buzz, they jump, they laugh, they even have faint inclinations towards love, but it is the hour of death, and paf! in the midst of the dance, they fall stiff. It is over, farewell to dancing!

I am sad here just the same. This absolute solitude, which has always been vacation and recreation for me, is shared now by a dead soul who has ended here, like a lamp which is going out, yet which is here still. I do not consider him unhappy in the region where he is dwelling; but the image that he has left near me, which is nothing more than a reflection, seems to complain because of being unable to speak to me any more.

Never mind! Sadness is not unhealthy. It prevents us from drying up. And you dear friend, what are you doing at this hour? Grubbing also, alone also; for your mother must be in Rouen. Tonight must be beautiful down there too. Do you sometimes think of the “old troubadour of the Inn clock, who still sings and will continue to sing perfect love?” Well! yes, to be sure! You do not believe in chastity, sir, that’s your affair. But as for me, I say that she has some good points, the jade!

And with this, I embrace you with all my heart, and I am going to, if I can, make people talk who love each other in the old way.

You don’t have to write to me when you don’t feel like it. No real friendship without absolute liberty.

In Paris next week, and then again to Palaiseau, and after that to Nohant. I saw Bouilhet at the Monday performance. I am crazy about it. But some of us will applaud at Magny’s. I had a cold sweat there, I who am so steady, and I saw everything quite blue.

To George Sand

Croisset, Tuesday

You are alone and sad down there, I am the same here.

Whence come these attacks of melancholy that overwhelm one at times? They rise like a tide, one feels drowned, one has to flee. I lie prostrate. I do nothing and the tide passes.

My novel is going very badly for the moment. That fact added to the deaths of which I have heard; of Cormenin (a friend of twenty-five years’ standing), of Gavarni, and then all the rest, but that will pass. You don’t know what it is to stay a whole day with your head in your hands trying to squeeze your unfortunate brain so as to find a word. Ideas come very easily with you, incessantly, like a stream. With me it is a tiny thread of water. Hard labor at art is necessary for me before obtaining a waterfall, Ah! I certainly know the agonies of style.

In short I pass my life in wearing away my heart and brain, that is the real truth about your friend.

You ask him if he sometimes thinks of his “old troubadour of the clock,” most certainly! and he mourns for him. Our nocturnal talks were very precious (there were moments when I restrained myself in order not to kiss you like a big child). Your ears ought to have burned last night. I dined at my brother’s with all his family. There was hardly any conversa-tion except about you, and every one sang your praises, unless perhaps myself, I slandered you as much as possible, dearly beloved master.

I have reread, a propos of your last letter (and by a very natural connection of ideas), that chapter of father Montaigne’s entitled “some lines from Virgil.” What he said of chastity is precisely what I believe. It is the effort that is fine and not the abstinence in itself. Otherwise shouldn’t one curse the flesh like the Catholics? God knows whither that would lead. Now at the risk of repetition and of being a Prudhomme, I insist that your young man is wrong. If he is temperate at twenty years old, he will be a cowardly roué at fifty. Everything has its compensations. The great natures which are good, are above everything generous and don’t begrudge the giving of themselves. One must laugh and weep, love, work, enjoy and suffer, in short vibrate as much as possible in all his being. That is, I think, the real human existence.

Read more from the letters of George Sand and Gustave Flaubert at Project Gutenberg.

DEAD WOOD provides excerpts from the years before ideas became “content”. Some editions are serious and thought-provoking. Some are ludicrous or silly. Some are chosen just because they happened to strike us as particularly interesting.

If you have an excerpt of “Dead Wood” you’d like to suggest, email Juke at tonyajuke@gmail.com

If you enjoyed this post, hit the ♡ to let us know.

If it gave you any thoughts, please leave a comment.

If you think others would enjoy it, hit re-stack or share:

If you’d like to read more:

And if you’d like to help create more Juke, upgrade to a paid subscription (same button above). Otherwise, you can always help with a one-time donation via Paypal or Venmo.

After having read these, marvelous, by the way, do consider 'For whom do you write?' to be one of the questions you consider for your next smorgasbord question. Just a thought,...

Gorgeous….have you been to: http://www.paris.fr/pratique/musees-expos/musee-de-la-vie-romantique/p5851 if not I suggest you do.